Drifting Between Perceptions: How Text Creates Distance in a Work

Author: Lin Pei-Yao

For me, the difference between text and speech lies in the fact that text can be separated from its writer (the speaker). When a reader absorbs words into their mind, the reader becomes a medium: through the act of reading, text transforms into speech and becomes part of thought itself. The question “Who is speaking?” can take on an ambiguous answer, precisely because the reader participates in the process of reading.

This perhaps relates to my own creative concerns: How can text guide viewers into activating a particular state of thought, and in a reflexive manner, allow them to experience a differentiated self? Under what circumstances can the speaking “I” and the addressed “you” overlap with the viewer’s own self, so that they imagine themselves as the speaker, becoming one of the characters within the script, rather than merely a passive listener—where the transmission of content becomes secondary?

The Distance Between Consciousness and Reality

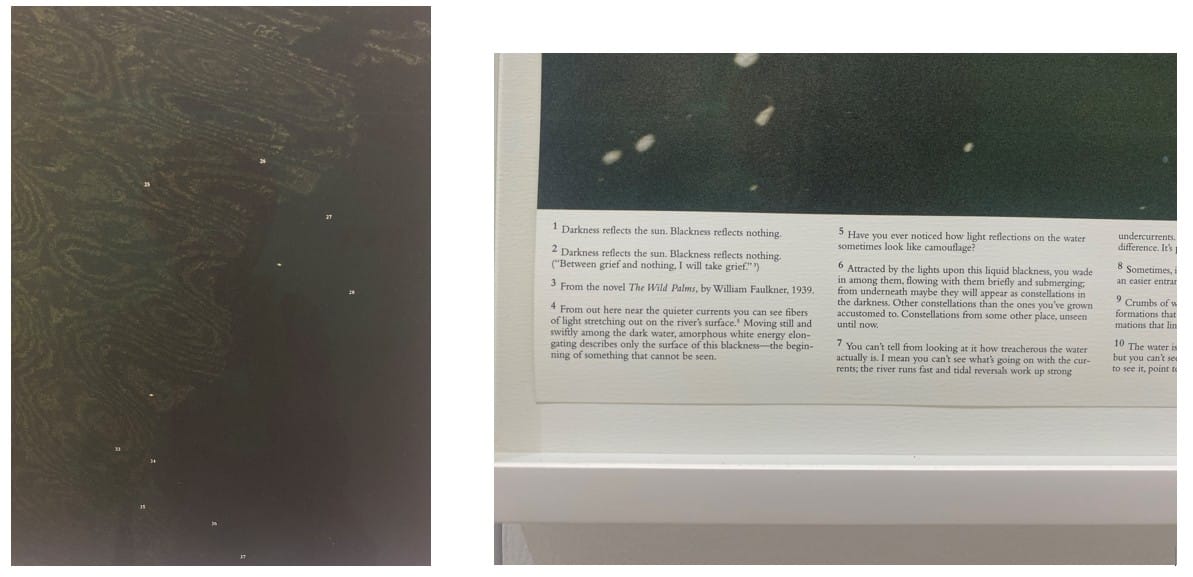

In 2023, Roni Horn held her first solo exhibition in Taiwan, presented at Winsing Art Place in Taipei. It was also my first encounter with her work, and I found myself particularly captivated by Still Water (The River Thames, for Example) (1999). I lingered before it for a long time. This series consists of six photo lithographs of the Thames, each paired with textual footnotes. The footnotes appear scattered across the images with no apparent order. Some are Horn’s own writing, while others quote from literature, film, or song, recurring in a poetic rhythm. By following the tiny numbers of the footnotes, viewers are guided across the water’s surface, examining its details, with their gaze moving back and forth between image and text.

At different points in time, we drift across different footnote markers, reading words about water, reflection, light and darkness, darkness and blackness. The writing shifts between first person “I,” second person “you,” and the concept of “self,” somewhere between direct address and inner monologue. Even though water itself is a neutral physical reality, we are unable to see through its surface—we cannot perceive the darkness beneath it—just as we cannot see through the shifting depths of our own inner life. This oscillating gaze, between image and text, resembles the process of self-reflection, while the still photographs condense the emergence of “self” in each perceptual moment.

The role of text in enabling such perception seems crucial, for it maintains a distance from the other elements of the work. Sophie Calle’s photobook Douleur Exquise (1984–2003) offers another example. In its first half, Calle overlays her daily snapshots—mundane images from her travels—with the harsh red imprint of a countdown. The accompanying text, written in a fatalistic, pessimistic tone, casts every trivial incident before a painful breakup as a foreboding omen. Here, the dissonance between text and image—between emotional intensity and the banality of the photographs—points to how cognition overlays memory with emotional filters over time. The gap between sensation and recognition mirrors the relationship between self and world, or more precisely, between consciousness and reality.

The Distance Between Self and Other

Turning back to the local art scene, I have noticed that Lee Kit in recent years rarely gives individual titles to his works (at least not ones disclosed to the public). Each exhibition feels like a single, indivisible work, only spatially partitioned into closer or more distant zones. His use of images almost completely absorbs me into a state that is both emptied and focused. (I even suspect this might be part of his criteria for choosing them.)

Take Retain a Desolate Face (Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts, 2022) as an example: a curtain drifting in the breeze, a used towel rolled and set aside, ducks swimming in a park pond, the sky and clouds. We look at these images, but in a sense, we are not really looking; what we experience is a kind of vacant, purposeless gaze into nothingness. The handwritten words, printed texts, or so-called “subtitles” that accompany the images resemble phrases that suddenly surface in the mind during a blank moment, or like an inner voice that has long been repressed finally breaking through—like bubbles rising from the depths of water. The sharpness of the words, paired with the ordinariness of the images, creates an estranged distance, reminding us of our alienation from the self within everyday life. Yet, in following the words to see where they might lead us, we find ourselves also staring at those aimless images for a long time.

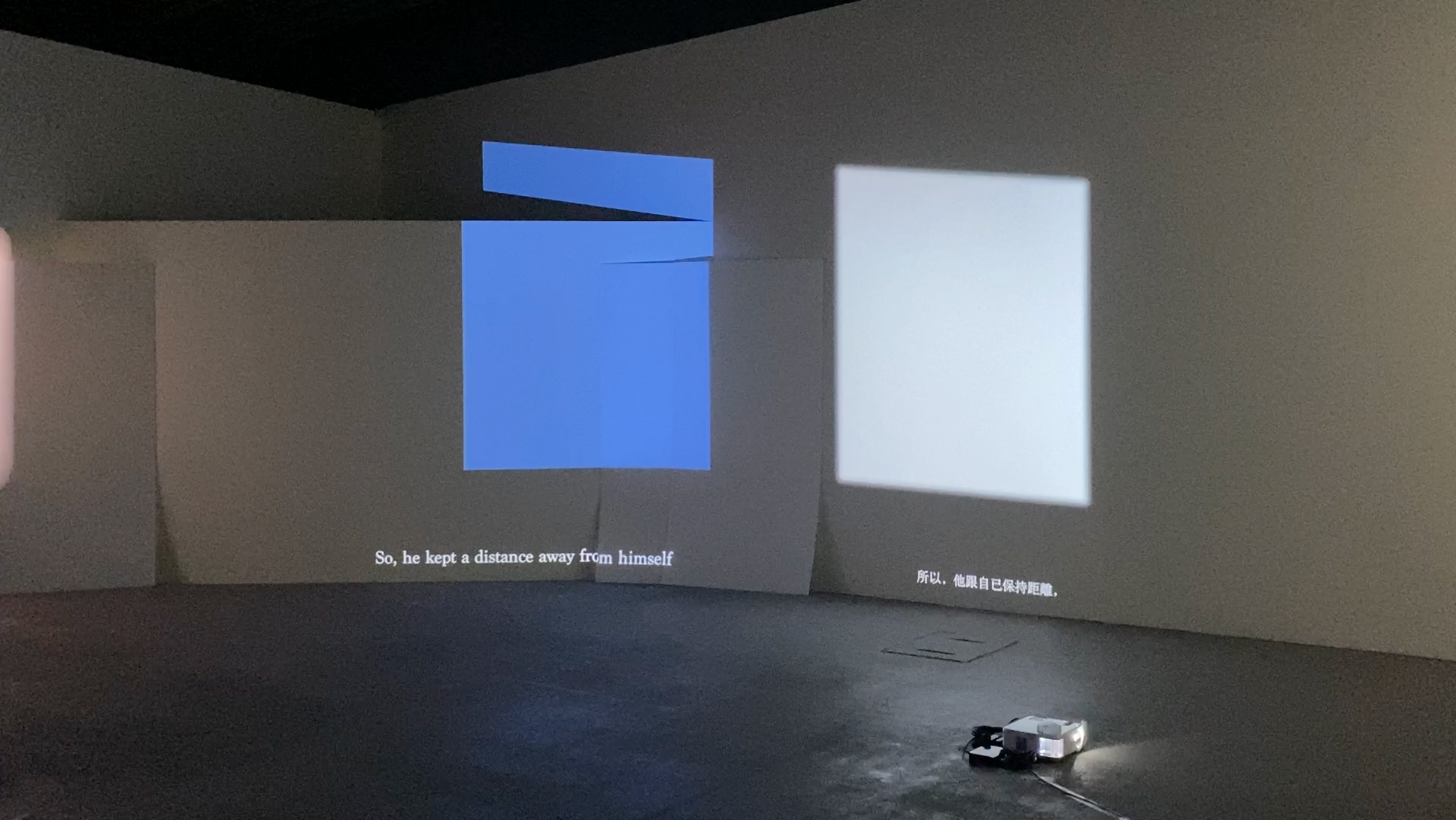

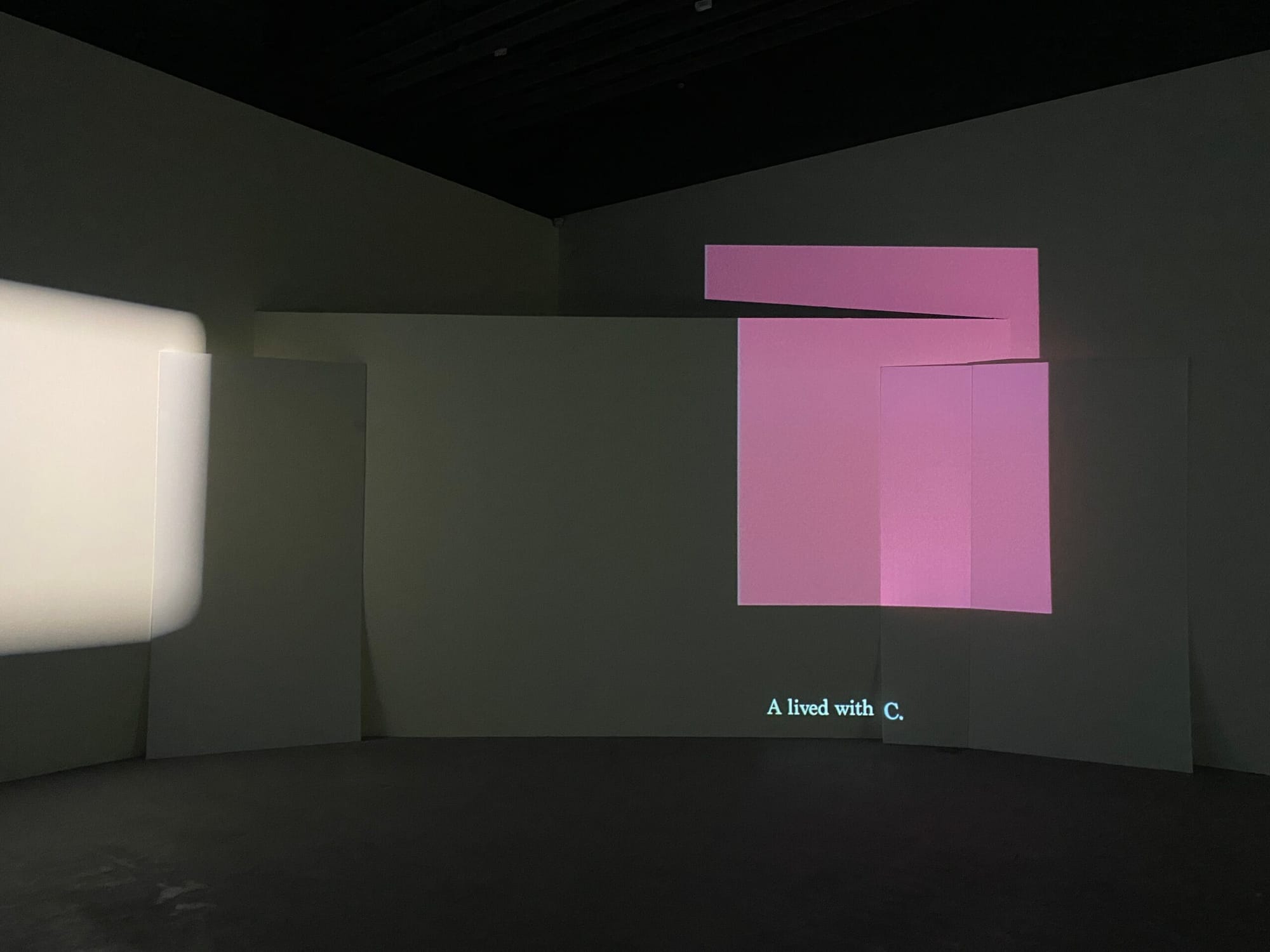

If estrangement from oneself constitutes alienation, then the alienated self also becomes, in some sense, an “other.” In Lee’s The Last Piece of Cloud (TKG+, 2023), a string of text in fragmented third-person narration describes snippets of daily life among three characters, A, B, and C, occasionally slipping into one of their thoughts. On screen, shifting blocks of white, blue, and pink appear alone or together, slowly overlapping, drifting in relation to each other, and then suddenly vanishing. The boundaries between characters seem indeterminate. Panels leaning against the wall slice up the space, allowing a single block of color to be fragmented into several parts, as if the characters’ selves are split once again. The subtitles have no direct connection with the colored blocks, yet in this unrelated juxtaposition, the blocks are assigned vague, indeterminate “roles.” They seem bounded but remain indistinct. The “I,” too, becomes a substitutable role, touching upon the relation with the other. “So, he kept a distance away from himself.” A, B, and C might be three distinct people, or perhaps only one person who has divided into three roles—keeping distance from oneself all the while.

The Distance Between Imagination and the Present

Through the use of text, Lee Kit creates in his works a detached vantage point of observation, allowing the viewer’s consciousness to drift between the present axis of sensory experience and the perceptual reality of the self. If his practice unfolds as a self-division within a work that cannot be broken apart, then the younger artists BLUE BUTTON (aka Yellow Dot Dot) and Jui-Tsz Shiu extend this further by anchoring their works in the viewer’s immediate presence at the exhibition site, deploying different media and spatial arrangements to make the viewer move back and forth among the present, memory, and imagination.

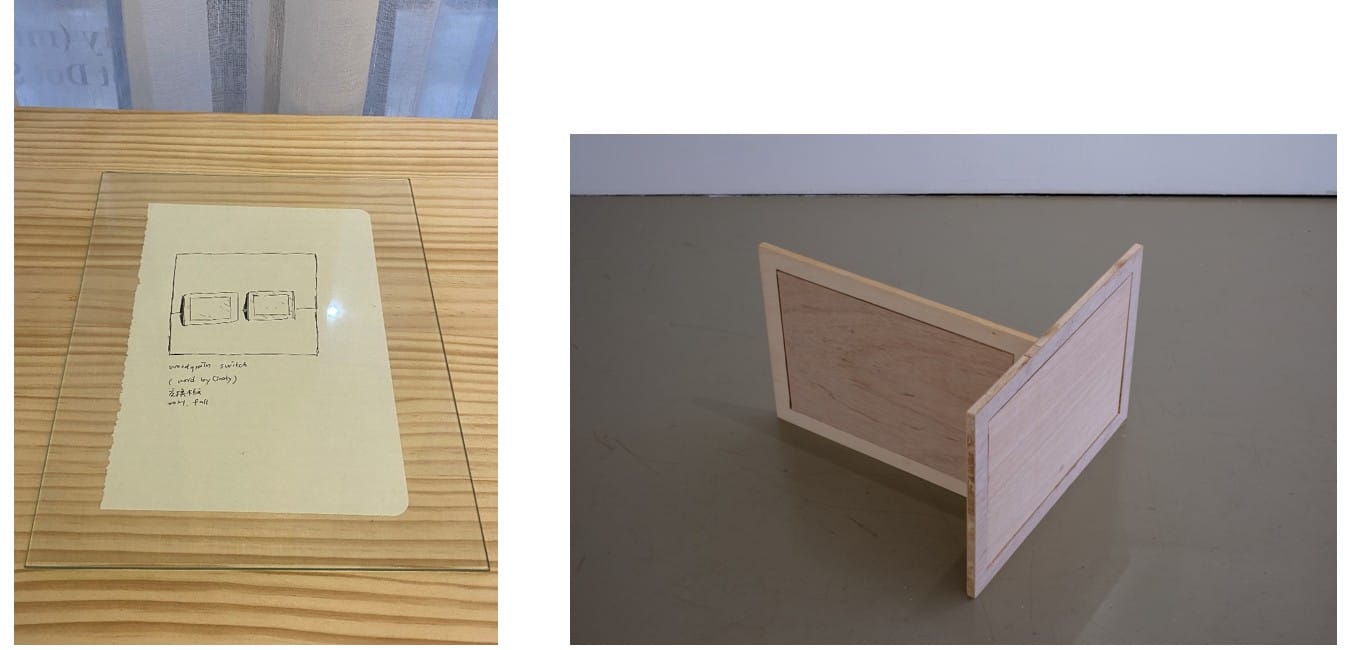

In BLUE BUTTON’s minimalist reflections on visualization and materialization, text plays a crucial role. In the exhibition About dirty (mistake) lemon yellow (Zone Art, 2021), the display included photographs, a two-image projection looping in a corner, a few small objects, framed sketches, a piece titled Sketch Desktop (so named in the floor plan), and a small booklet of texts that would reappear in later exhibitions. The page numbers of the booklet loosely correspond to the arrangement of works in the floor plan, allowing the viewer’s thoughts to shuttle between the booklet’s textual descriptions, the objects in the space, and the sketches, searching for connections.

Take the work Exchanging Wood Grain as an example. On the Sketch Desktop, there is a paper sketch depicting two wooden planks positioned at a right angle, each exchanging part of its grain with the other. While the drawing suggests a perfect exchange, the actual construction necessarily leaves a gap where the saw has cut. “This is a work that is fundamentally impossible,” the artist writes in the booklet. Here, text becomes a medium for the “impossible,” while the physical and visualized objects in the exhibition serve as imperfect counterparts—yet it is through this very contrast that the state described in the text acquires a kind of relative perfection.

In BLUE BUTTON’s exhibitions, there is no fixed hierarchy determining whether text, sketch, or object is annotation, supplement, or cause-and-effect. She even directly describes the discrepancy between them in her texts: “I really can’t seem to make all these fascinating things come out.” Elsewhere, in a section titled Parking Lot, she writes: “I thought the things I failed to capture looked different from this winter’s memory.” This passage corresponds to a blurred photograph taken in a parking lot, A Work Borrowed from S. Without further explanation, the pairing invites us to wonder: What was originally meant to be captured? What was that winter in memory like? And how does this differ from the photograph?

On the one hand, present material reality seduces us by being more elusive than imagination; on the other hand, once the present slips into the past and memory becomes unstable, the poetic states that can only be described in words or sketches reappear, mirroring the insufficiency of material reality itself. Within the space stretched open by such discrepancies, viewers weave between booklet, sketch, and object, evoking the montage-like perception of time in everyday thought. Imaginary experiences, never fully materialized, quietly become carriers of the work. After all, how could one ever “describe the shifting of a remembered color and light”?

In Jui-Tsz Shiu’s The Ways to Pack (FreeS Art Space, 2023), the exhibition also included a booklet, 5 Ways to Pack (2021). Most works could be loosely related to the booklet’s fictional character “S” and her stories. For example, in the video installation Lost House, a woodland photograph printed on canvas, with the shape of a house cut out from its center. Dash cam footage from the road leading to the site, and a recording of an elder tracing the outline of a house with her hand, all evoke the second chapter of the booklet, which recounts S’s grandmother’s old home—never visited by S herself, only told in stories, and now gone.

“Packing” in Shiu’s exhibition refers to how perception and memory of a space can be carried elsewhere, unfolding through the body as medium. In the booklet, the first-person “I” narrates, while S’s story is told in the third person, describing her practice of packing bodily sensations and memories. S can only imagine the places she wants to pack through her own experience, and the narrator can only imagine the stories that S recounts to her. The works in the exhibition space extend this process further: the artist, returning to herself as “I,” imagines and re-imagines the places that S imagines. Even though both S and the first-person narrator are the artist’s inventions, the voices multiply: S’s “I,” the narrator’s “I,” the artist’s “I,” and perhaps the viewer’s own “I.” These layered perspectives on space overlap, diverge, and intersect within the act of reading at the exhibition.

For me, even after reading the booklet at the start of the exhibition, I did not feel that the show was a direct visualization of the text. Rather, because I had already imagined the five places that S wanted to pack into her body, the later works appeared in contrast with those prior imaginings. The exhibition space opened up a dialogue between imagination and reality, so that my experience was one of drifting back and forth between what I had pictured and what I now encountered.

The Gap Between Sensation and Cognition

I believe that the potential of text as a medium in artistic practice does not lie merely in its narrative or explanatory capacity to integrate other elements, nor simply as documentary supplement. Rather, it lies in its ability to deliberately preserve a distance of difference, to be placed alongside other media while creating contradictions, mismatches, or seemingly irrelevant gaps. Text often plays the role of an independent agent, carrying a reflexive detachment that resists merging fully with other elements. At the very least, it maintains the presence of one or more voices or “others,” producing within the work a subtle discordant echo, an internal counterpoint that never ceases to engage.

The spaces, still and moving images, and objects within such works then form referential relationships with the text, marked by disjunctions. At first glance, these juxtapositions may appear incidental or arbitrary, but at certain points faint connections emerge, continually testing the threshold between “related” and “unrelated.”

Within this distance, the paradoxical qualities of text—both empty and full—are revealed. Empty, because what it describes can be freely imagined, connected, and extended. Yet full, because each word, once written, is easily saturated with countless symbols, connotations, and personal memories, flowing into the work like water finding its way downhill. Unlike visual or material elements, which tend to draw viewers into comparable sensory experiences, text unfolds into diverging pathways of imagination, distinct for each reader.

In this way, the viewer is not only experiencing within the work, but also becoming aware of the flow of their own consciousness—leaving and returning, again and again, drifting between the sensory immediacy of the present and the interior space of perception. Out of this drift, multiple temporalities of experience may arise.

Translation: Lin Pei-Yao

Responsible Editor: Yung-Wei Tung

This article was first published in CLABO, 2024.